Jeff Kindler was a rising star in the legal world. After getting a Harvard law degree he worked at the FCC, clerked for a Supreme Court judge, and made partner at a big D.C. law firm. After that he went corporate, becoming GE’s head of litigation and Executive Vice President and General Counsel at McDonald’s and then Pfizer.

In 2006, Pfizer made Kindler CEO. Four years later, he was forced out by the board. Why? This wasn’t just any company. This was Pfizer, a pharmaceutical giant with its top products going generic and a dried-up drug pipeline in need of a major overhaul. It was a tough job and, in my opinion, Kindler was in over his head. It happens all the time.

Since our society loves silver bullets and sound bites, there’s a word and a phrase we often use to describe this sort of thing. The word is “hubris,” meaning “exaggerated pride or self-confidence.” The phrase is the “Peter Principle.” It describes how employees tend to rise to their level of incompetence.

If you want, we can just leave it at that and call it a day. It’s less work for me, that’s for sure. But then, I wouldn’t be doing my job. Slapping a label on it doesn’t solve anything. It doesn’t explain how this sort of thing can happen to otherwise capable and successful leaders. And it definitely doesn’t help us or our companies avoid that fate.

What makes hubris and the Peter Principle particularly insidious is this. When you’re on the rise, climbing the corporate ladder like some crazed corporate monkey, you’re not the least bit interested in hearing about your shortcomings or limitations. And after you’ve flamed out, it’s usually too late. Usually, but not always.

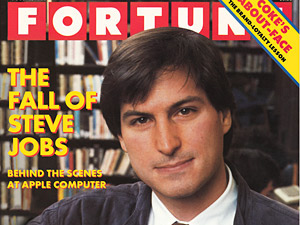

Steve Jobs was famously booted from the company he co-founded, Apple. And while he didn’t see it at the time, 20 years later he said, “getting fired from Apple was the best thing that could have ever happened to me. It was awful-tasting medicine, but I guess the patient needed it. Sometimes life hits you in the head with a brick.”

Who knew that a brick could be such an effective tool for mentoring dysfunctional executives? Oddly enough, that’s exactly what works. In many cases, it’s the only thing that works. That’s because leaders develop in much the same way that people grow from children to mature adults.

You see, when you’re a little kid, you think the whole world revolves around you. You look cute and cry and, like magic, stuff comes to you. Which is a good thing, because manipulating adults to take care of you is an important survival mechanism.

But as you age, you come to realize that the world is a very big place, people have lots of stuff going on, and nobody gives two beans about you. You eventually figure out that getting what you want ultimately depends on you and nobody else. That’s called self-reliance and personal responsibility. It’s essential to becoming a mature adult. But some people never learn that important lesson.

Their level of maturity is stunted and they remain entitled little brats. They jealously covet what others have. They act out and throw temper tantrums when they don’t get what they want. They look and dress like adults, but inside, they’re still children. And they make lots of mistakes.

It’s the same thing with leaders. Many, if not most, first-time managers start out a little full of themselves. After all, power and authority is pretty heady stuff. And the careers of hotshot up-and-comers are usually filled with risks that pay off big-time, all sorts of accolades, and inevitably, lots of money.

But experience usually teaches us a few lessons along the way. Lessons that help to temper all that stuff that feeds our egos. While we gain self-confidence from success, we also learn humility from failure. With the right feedback, we gain wisdom and maturity. And sometimes, we even need a brick to the head to wake us up. But some leaders never learn that important lesson.

Success makes them think they can do no wrong. They think they have all the answers, that they’re untouchable. Of course, none of that’s true. We’re all flesh and blood humans. We all have our issues, our weaknesses, our limitations. And sooner or later, we make mistakes. Sometimes big ones.

We take huge risks based on assumptions that aren’t justified. We take on challenges we’re not prepared for. We surround ourselves with yes-men who sugarcoat the truth and tell us what we want to hear. We come up with grandiose visions that aren’t logical. We pitch megamergers that are fraught with risk like they’re no-brainers. And eventually, it catches up with us.

Now, you can call it hubris or the Peter Principle if you like. You can call them greedy CEOs or slimy politicians. But if you do, you’re not getting to the heart of what’s really going on. You’re just slapping a label on it, washing your hands of it, making believe it’ll go away. But it never does.

You see, leadership is a lot like growing up. If we don’t teach kids self-reliance and personal responsibility, they never grow up to become mature adults. And they make lots of mistakes. It’s the same thing with leaders. When we don’t hold them accountable for their actions, they make mistakes – big ones that cost us more than we can afford.

Note: Kindler is now CEO of Centrexion Inc.

A version of this post first appeared on my Critical Thinking column at FoxBusiness.com.