Finally, a social media pioneer fesses up to the truth in a startling revelation: that Facebook’s founders weren’t just consciously aware of their product’s addictive potential; it was the goal of Mark Zuckerberg and company to “consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible.” And they succeeded beyond their wildest expectations.

The strategy, according to Facebook’s founding president Sean Parker, who spoke at an Axios event yesterday, was to “[exploit] vulnerability in human psychology” by giving users “a little dopamine hit” when someone likes or comments on a post. “It’s a social-validation feedback loop,” said Parker. “The inventors, creators … understood this consciously.”

I explained the biological backstory and sociological implications of the mechanism Parker describes in Chapter 3 of Real Leaders Don’t Follow. Parker’s surprising admission validates one of the book’s key premises, a phenomenon I call the “Idiocracy Effect,” after the cult classic Idiocracy. Here’s an edited excerpt:

Millions of years ago—long before we evolved frontal lobes and the ability to think rationally—we were creatures of instinct and emotion. We were all about survival. And that meant eating when food was available, seeking out shelter and safety in numbers, and, of course, pursuing members of the opposite sex.

Since we were unable to reason logically, our brains produced powerful neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin that induced a narcotic-like euphoria to reinforce those behaviors critical to survival. In other words, meeting one of the survival imperatives was rewarded with biochemical reactions that made us feel good.

That behavioral reinforcement mechanism helped us to evolve as herd animals and as social creatures. In the meantime, our brains continued to evolve, eventually adding a neocortex for higher-level thinking. We became more social but also more organized. Our communities became larger, more complex, and more civilized, generally speaking.

But beneath the folds of gray matter, buried deep in our subconscious minds, still lies the brain of a caveman. The limbic system, the feeling and reacting portion of the brain, regulates involuntary and hormonal functions, including the adrenaline fight-or-flight response to emotional stimuli.

After all this time, the limbic system is still responsible for our survival. It still reinforces the same behavior through the same powerful mechanism. To the limbic system, not much has changed over the millennia.

In particular, the limbic system strongly reinforces the sort of social behavior that enabled our survival long ago by making us feel good when we eat, have sex, are sheltered, and socialize with others. While we’re usually unaware of the effect, it’s always there. And it deeply influences our behavior in profound ways.

The system worked quite well until we became a socially connected online world. Now we’re all feeling that powerful tug to text and tweet – to desperately seek attention and followers – because biochemical reactions in our brains give us pleasure when we do. It’s the same process as any addiction. And it’s the same process that makes lab rats continuously press a lever to get food in B.F. Skinner’s behavioral conditioning experiment.

Today, for the first time in history, we can satisfy our most basic needs at the click of a button or the tap of a display. So that’s what we do. Over and over again, just like drug addicts or lab rats in a Skinner box.

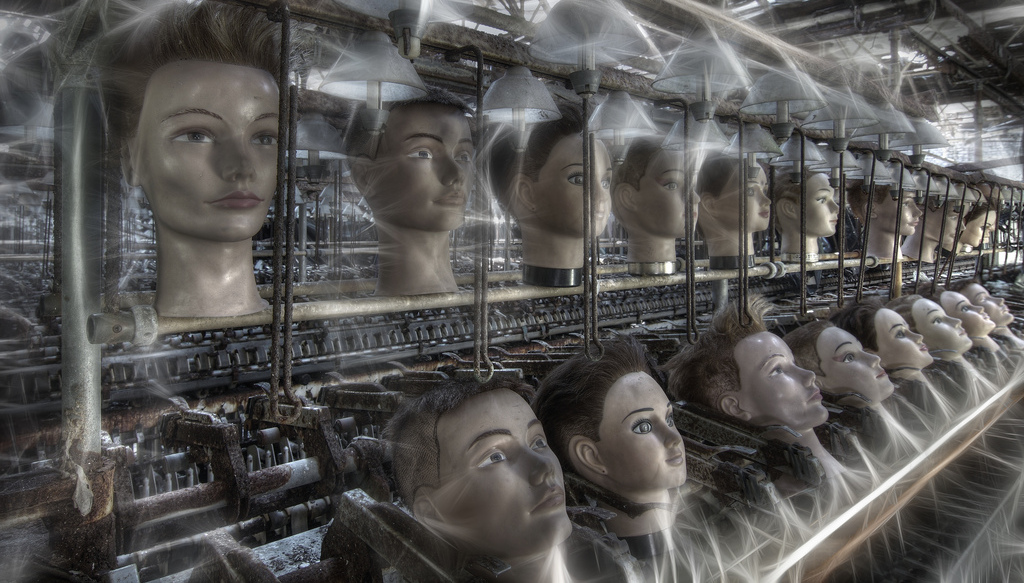

In short, the nearly irresistible tug of the socially connected world is causing us to revert back to ancient instincts. Behaviorally and organizationally, we are indeed devolving. It’s dramatically affecting our culture, including the way we live and work. I call it the Idiocracy Effect. Unlike the movie, it’s not fiction. It’s absolutely real. It’s affecting each and every one of us in ways we’re not consciously aware of. And it has far-reaching implications.

Parker says he doesn’t know if he really understood the consequences “of a network when it grows to a billion or 2 billion people” at the time. “It literally changes your relationship with society, with each other. It probably interferes with productivity in weird ways. God only knows what it’s doing to our children’s brains.”

Now he tells us.

For more on the “Idiocracy Effect” and the impact of social networks on how we live and work, pick up a copy of “Real Leaders Don’t Follow: Being Extraordinary in the Age of the Entrepreneur” today.

Image credit Bousure via Flickr